ED’S INTRO

Offshore drilling and shipping have attracted lots of interest among resource investors this year. Imagine if you could invest in companies which combine the two!

Well, you can. But the specifics of the offshore support vessel market can be intimidating. To help people get started, I transcribed a superb recent webinar by Fearnley’s Securities.

Note: The market for PSV’s, i.e. platform supply vessels, is divided into distinct geographic territories, with their respective supply and demand dynamics. The advantage of the North Sea market (= the UK and Norway) is that there are several companies which are essentially “pure plays” — mostly listed on the Oslo Stock Exchange — which allow you to focus your attention on that particular market.

Enjoy!

— Ed

Axel Benvold, Head of Project Finance at Fearnley Securities

The offshore support vessel market has turned from distress to high earnings in the last 18 months. Offshore oil and gas infrastructure continue to offer energy security globally, and we now see the consequence of the last seven years with underinvestment in these segments. Subsequently, the OSV assets have appreciated in value and we have now entered a full recovery, which is expected to accelerate in the coming years. Fearnley Offshore Supplies Analyst Theodor Sørlie will do a presentation on the North Sea market to provide further context into the market drivers and the forward-looking market balance.

Theodor Sørlie, Fearnley Offshore Supply Market Analyst

For the purpose of this session, we will focus primarily on the PSV market in the North Sea. We'll also look abroad and look at what's happening in regions such as South America, the Middle East, Guyana, and see how that can have an effect on our home market. We'll go straight into how valuations have developed in the segment over the last couple of years.

Please keep in mind that this is non-age adjusted valuations, so this is just the broker valuation of a vessel at the time of the valuation being given. What we see is, of course, that the market starts to deteriorate from the end of 2014 onwards, and those assets reach a bottom in 2021.

On the left-hand side here, you see a basket of seven large Norwegian built PSVs and they bottomed out in December 2021, where we put the fair market valuation on those at just shy of 1 billion Norwegian Kroner, where they had an average age of eleven years. In March 2023, last quarter, we put a fair market valuation on the same vessels at 1.4 billion, and the average age had increased by two years. That's a 46% appreciation, while the age has gone up quite a lot. How could this happen?

Similar for mid-sized PSVs, ranging from 650 to 850 square meter deck size, they experienced an even more dramatic increase in valuation from about 560 in the middle of 2021 towards over $1 billion in the last quarter, which represents over 80% increase, while the average age has gone up to 14 years. We'll go back to how the effect on this has been on the age adjusted valuation as well, but I think this sets quite a good framework for the discussion just to showcase this is what's happening, this is how people are valuating their vessels and how could this happen and what's the remaining upside in the market?

So, going into the North Sea market, we see that—currently, utilization of the PSV fleet is about 95%. It's been trending there since the start of the year. You have no vessels in layup as of now, so the excess capacity locally is completely taken out of the market and there's no newbuilding, of course.

An interesting development is that the North Sea fleet is the lowest in a decade. So, it was peaking at about 275 vessels, and we're now down to less than 180 vessels totally. So, the utilization is actually not driven by extremely high activity levels, it's driven by lack of suitable tonnage.

[The] North Sea basin is now at the point where the number of rigs on contract is still far below what you saw in 2012—14. But it's sufficient to drive utilization towards a 100% because the fleet is so small.

Back in 2017, at the height of the crisis, you had over 120 units in layup in the North Sea. It's fair to also mention that the North Sea served as a basin to cold stack your vessels and then they went into other regions to work once they got reactivated, and there's been a fair amount of scrapping. So older tonnage — where you decide that, it's not economically viable to do the reactivation — you simply sell them either to a distant region where they can operate for maybe two more years, or you scrap it.

We have [now] established that the valuations are rising. The fleet is at the lowest level it's been in a decade, and activity levels are not that high today. But still, the fleet is basically sold out. So, what do we expect going into the future?

As I mentioned, here at the top left corner, you see that we now have the lowest fleet with almost 100 vessels going out of market, an average age of almost 13 years. There’s no newbuilding activity and we don’t record any official newbuilding orders on high spec North Sea tonnage as of today. When you track the oil and gas investments on Norwegian continental shelf is expected to increase by 22 billion Norwegian kroners this year and remain stable at about 180 billion in the coming years, resulting in increased production from Norwegian continental shelf.

So back in January, February, when the Norwegian Oil Directorate came out, with forecast going forwards, they expect to increase the production on Norwegian continental shelf by 8% from 2022 going into 2025. And if we go past the 2025 period and look at the PDOs submitted last year, primarily driven by Aker BP, they amounted to over 250 billion Norwegian kroners.

The majority of those PDOs will go for projects that go live from 2026 and 27 onwards and that's creating a strong backlog of activity, ensuring that the North Sea fleet will have strong employment prospects going towards the end of the decade.

As I mentioned initially, the drilling activity in the North Sea, both the Norwegian side and the UK side, is not incredible this summer. So today we expect about 50 rigs total on contract across both floaters and jack-ups active from May until September [2023]. That’s less than last year. We had about 55, and it's about the same as the summer in 2021.

However, from next year, especially driven by jack-up activity in the UK, both for exploration and the decommissioning, we're expecting that figure to be close to 70 rigs on contract.

So in our modeling we're looking at, okay, what’s the consequence of having an additional 20 rigs on contract with the fleet that’s the lowest in the decade and basically no more excess capacity as of today. And that's quite an interesting modeling because you see quite quickly that you're heading towards an extremely sold-out market. We basically need to import vessels to service the local demand, which is exactly the opposite of what's been happening in recent years where vessels have been sold out of the North Sea market to be employed in high activity regions such as Brazil, the Middle East, Guyana.

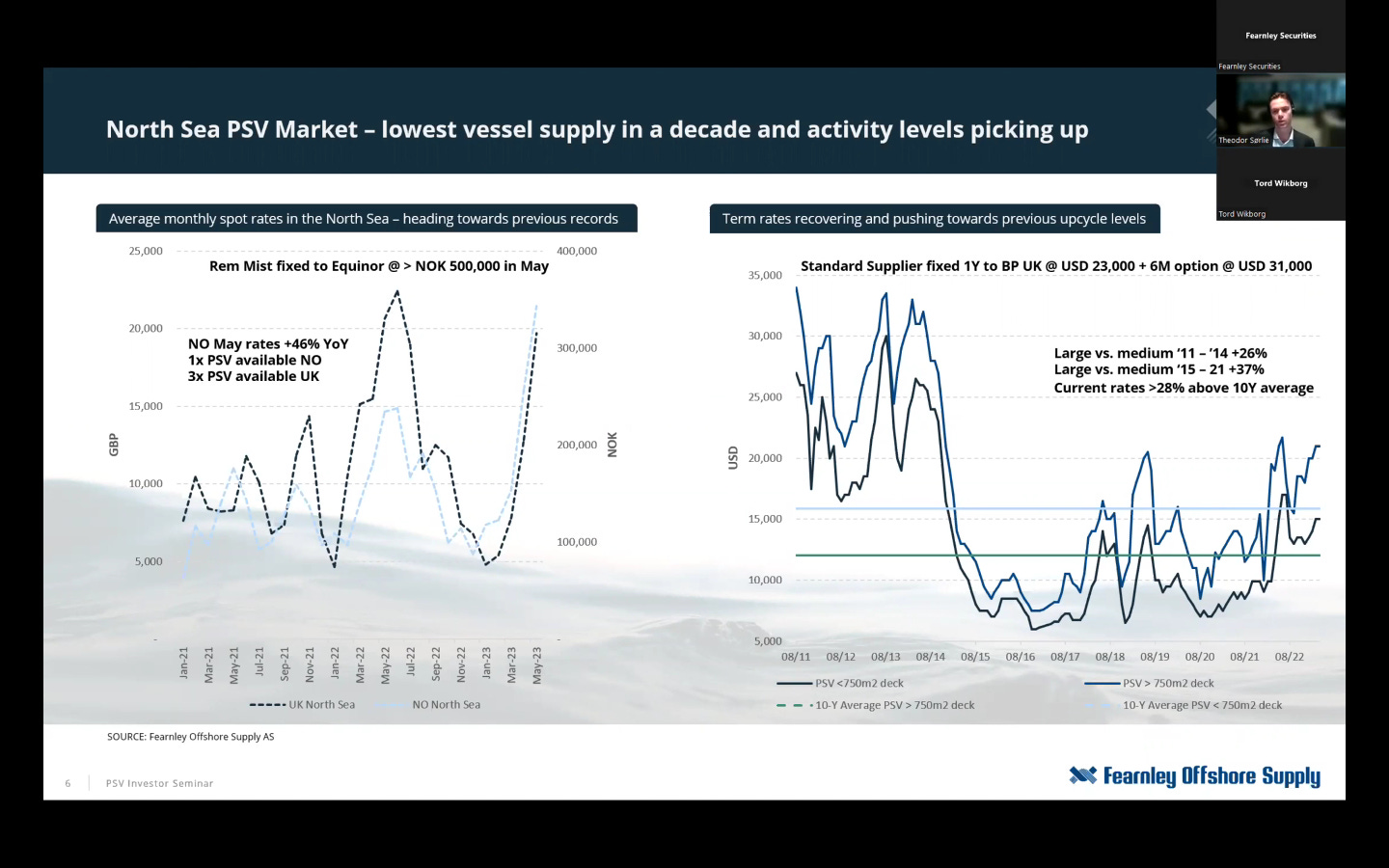

And what's happening to the rates these days? So, on the left-hand side, you can see spot rates both on the UK and Norwegian side of the North Sea. My colleague Jesper [Skjong] had a conference back in February this year, where he predicted that the spot rates on the North Norwegian side could reach as high as 500,000 Norwegian Kroner.

He was deeply criticized by people in the industry because that was way too aggressive, people said. But last week we actually saw Equinor having to fix Rem Mist [IMO 9521667] at over 500,000 Norwegian Kroner, even though it's still for one day. Because it's illustrating when the shortage appears, the operators have no other choice than take the vessels available.

As of today [i.e. 1 June 2023], the North Sea market on Norwegian side has been sold out since the beginning of May. There has been few transactions or few fixtures, but the average fixture rate has been almost 350,000 Norwegian Kroners. On the UK side, you had better availability, less rig moving activity, so you had spot rates almost reaching 20,000 British pounds. Still considerably better than in recent years.

It's fair to also say that these rates cover only the month of May. While going into June has historically been the highest activity levels where the operators accumulate rig moves and they go out and take what's left in the market. So we could expect to see some of these rates move into territory that we haven't seen since back in 2012, 13, 14, when the tightness was prevalent and owners generated very strong cash flows.

In the term market, which we define as more than 30 days firm contracts, you see also quite a dramatic increase in rates over the last 12-18 months. The current term rates in the North Sea are about 28% above the ten-year average across both large and smaller vessels. And today one of the publicly traded vessel owners, Standard Supply, they reported a one-year fixture with BP UK at $23,000/day and six-month options at $31,000/day.

If the market continue to move in the direction we expect, it's likely that BP will need to take out those options and then you see that the rates that we have today is quite interesting going into the period that we're expecting.

An interesting development as well is the difference between large and medium sized PSVs. Obviously, large PSVs can demand a higher rate on average, but what we're seeing is that when the market is tightening, the delta or the premium that the large PSVs are able to demand declines. So in the “poor years” with extremely loose markets, a lot of vessels available, the average premium for large vessels compared to medium sized ones was 37%. However, in the tight years, from 11 to 14, that was 26%. That's giving you an idea that when you are a charter and you're operating in a market with lots of vessels available, you're basically able to cherry pick whatever you want.

But we're now moving into a period where it's more likely to see higher rate increases also across the medium section, even though—you, as an operator in the poor times will choose the larger assets. So, they had stronger utilizations during the downturn and managed to have more stable valuations throughout the last couple of years.

I also mentioned that we don't see any newbuilding: what's the reason behind that? There’s a lot of talk that it's not possible to build new today because it's costs too much. It takes too much time and the financing is quite challenging for most oil and gas operators.

What we've done here [above] is to showcase how much equity is priced in the market compared to the cost of building a new Norwegian built PSV [with a deck of] 1000 square meters. So, on the top right-hand side here, you can see the market cap of a selected set of publicly traded offshore owners. And you can see how many new builds of large Norwegian built PSVs which will be future-proofed with alternative fuels they can afford based on that market cap.

I find it quite interesting because it puts it into a quality relative space and it kind of make you understand that Solstad Offshore has a market cap of about 2 billion Norwegian Kroners as of last week. They can only afford with that equity to build 3.3 modern Norwegian 1000 square meter PSVs.

We know also that the rates are not sufficient to justify the new builds. We know that to justify one of those new builds mentioned, 1000 square meter, 70 million USD price, you will need over $35,000 on a 15-year period to give about a 12% return on equity or on capital on that vessel.

Today, the rates are below this level and it’s very unlikely that operators would give those kind of long-term contracts, leading to the incentives for speculative new builds to be severely limited.

If some of you have experienced from oil and gas investments in recent years, it's quite obvious that banks have been scaling down investments, it’s hard to refinance. We also see that most of traditional owners in offshore support markets, they have existing debt. So when the earnings now come, they will likely use that earning to repay existing debt and potentially treat their shareholders with dividends in the medium term. Extremely unlikely that banks will be able and willing to finance new capacity in the market.

On top of that, the construction time has increased quite dramatically depending on where you build and when you build and what kind of vessel you build. It’s ranging from two to three years increase in terms of construction time for a modern PSV. That means that if you are lucky to get the financing by the end of this year, it's very unlikely to see any real supply additions until the end of 2025 or early 2026.

The yard capacity in some places, such as China, which has been a major builder of PSVs, is also quite tight, driven by conventional shipping. And you also see parts and equipment being dominated by delays. So it's hard to get the correct equipment reactivations in recent years has led, for instance, [one shipyard], to reduce their inventory of key equipment needed to build these kind of vessels.

And lastly, the new building cost has increased rapidly. So today building a PSV in a Chinese yard, which is the only place we update the points for the last couple of years because there's been no new building in Norway since basically 2014, it's increased about 30—40%. Of course, in USD terms Norway will be favorable, but it's quite pricey compared to the alternatives.

So in conclusion, we're seeing new building very unlikely among traditional offshore owners. You might have opportunistic capital available to some. But for the major owners, as example, listed here, to push or pull the trigger on a new build on modern high spec Norwegian tonnage is extremely unlikely.

We have now established that the North Sea is a region where you have medium activity but still a sold-out market. Rates are moving quickly. Let’s look outside of the North Sea. Can there be any supply coming from other regions?

What we see globally is that the total spending on both maintaining, existing production, and funding new exploration is increasing rapidly. So, in 2022, you spent about 7 billion on total E&P spending to both new field activity and existing production and that's going to increase to almost 12 billion towards the end of next year. This is in a market where the supply is the same.

What’s very interesting when looking at that spending is that the majority of spending is sanctioned for next year and 2025 and 2026, and what's not sanctioned towards 2027 requires break even oil price of less than $60. That's a testament to the oil majors who have gone through efficiency processes, who have really done well in terms of cutting costs and becoming leaner and more efficient. They can operate at the revenue level as much more competitive than during the last upcycle and building.

That's why we're confident that even if the oil price takes a bit of a slide due to geopolitical uncertainty or potentially also a reduction in global demand from a mild recession, you see that OSV activity is going to remain somewhat high, at least within the time horizon that I'm presenting here.

A key takeaway looking outside of the North Sea is that the rates achieved are higher than in the North Sea. So, you're getting a premium when you're trading a large Norwegian built PSV in Brazil, Guyana, West Africa or the Mediterranean. Today, the average global term rates on larger units are just below $30,000/day, while the medium sized ones are just below $20,000/day. That's a couple of thousand higher than the North Sea. So owners are able to capture or benefit from that extremely high activity level compared to the North Sea. And you see that with rigs moving out of the North Sea into different regions such as West Africa and Australia, and then it's likely that vessels are following.

Similarly, to the North Sea, you've also had quite a high increase in rates compared to the ten-year average. So as of May, these rates are about 50% higher than the ten-year average. But keep in mind that of those ten years, at least seven of them have been struggling.

Diving a bit into the Brazil or the South American market — because that’s been the highest activity in terms of total offshore vessels needed to maintain and scale up new production — the E&P vessel spending in South America is extremely aggressive. They’re going to spend more than 1.4 billion more on vessels until 2027 and Petrobras has approved the CapEx program on E&P that will add 7 and a half billion in spending from last year to next year.

What you're also seeing is that the total PSVs and anchor handlers in South America is reaching its all-time high, so they're about 38% up from 2018, and that's, of course, leading to a tight Brazilian offshore market. Today, the PSV market is pushing towards sold out. They’re actively seeking vessels from different regions trying to secure enough tonnage to meet future Petrobras tenders.

From 2023 or this year to 2027, they're expected to increase the number of active FPSO from just 74 today to 89 going forwards, which is absolutely incredible when you look at the offshore needs needed for a single FPSO deployment. And that's, of course, translating into higher rates. So the rates in April are about 30% higher than last year average and 40 additional PSV needs going into next year by Petrobras alone.

I don't know where these vessels are going to come from because as of today you look at different regions and they're all starting to tighten and whatever excess supply is left in the market, being cold stacked, is normally quite old and of poor technical quality. So, most likely consequence is that they will have to lower the specs and lower the requirements to basically fill those OSV needs.

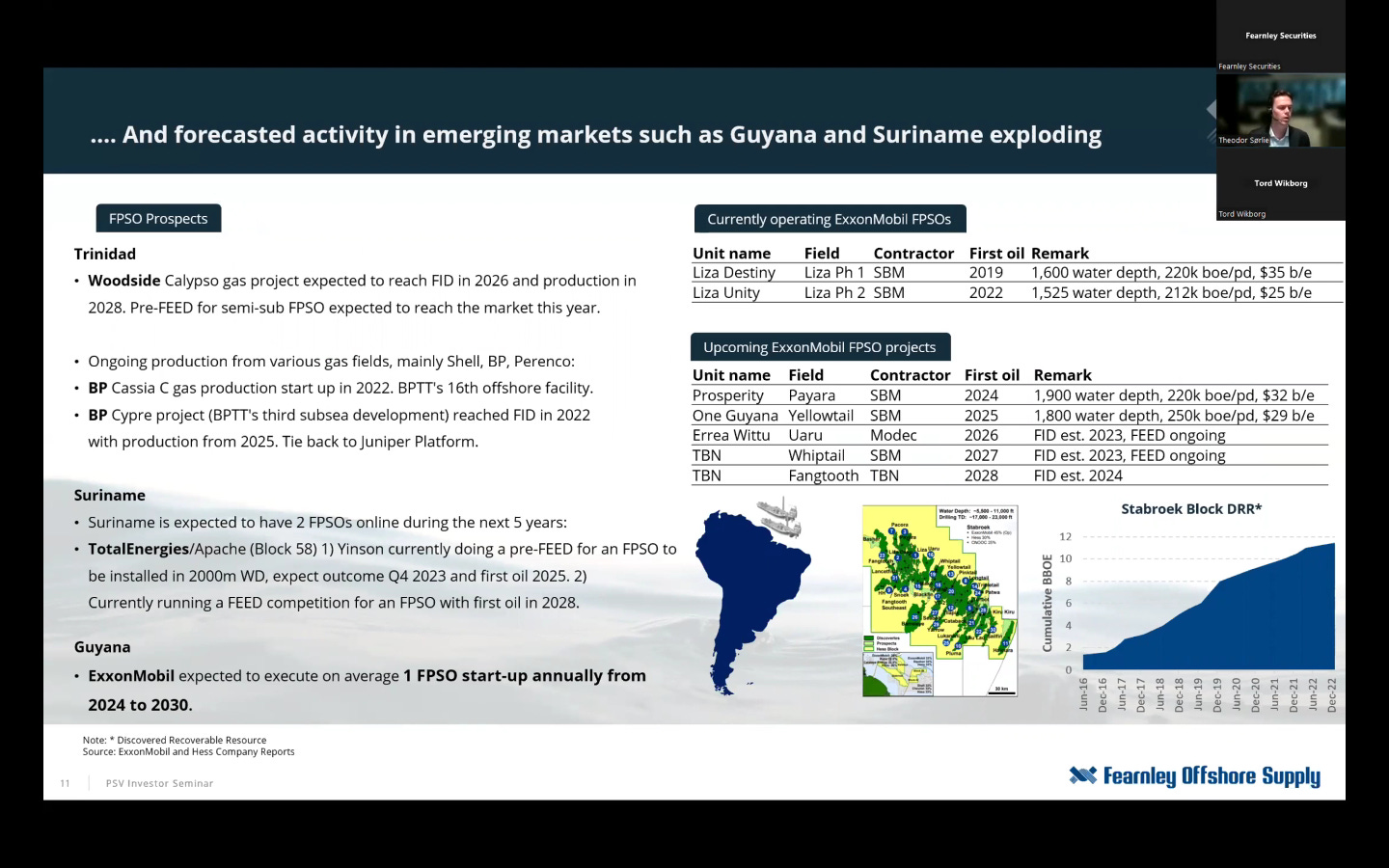

Emerging markets are also quite interesting. We’re working on understanding the markets in Guyana, Trinidad, Suriname and the key takeaway here is that these new discovery markets are going to take a lot of offshore needs and they have had zero previously.

So, for instance, in Guyana they have two FPSOs active as of today. They expect one FPSO deployment annually up until 2030 and very limited local fleets. That fleet is going to have to come from either North — being the US Gulf where they have call it a pricing monopoly on rates — or South, meaning Brazil which is firing. So, it's very likely that these vessels could come from the global pool, for instance, North Sea tonnage, creating even more upward pressure on the rates.

A key consideration on these projects is also the [oil] breakeven cost. So, when you look at the existing infrastructure they deployed the two FPSOs, they have a breakeven cost of between $25 and $35 on those FPSOs. Going forward, it’s ranging on the one I have disclosed between $32 and $29, which is quite impressive and also gives confidence that the offshore spending and needs will be maintained because the profitability and cash flows generated from these assets is so extreme.

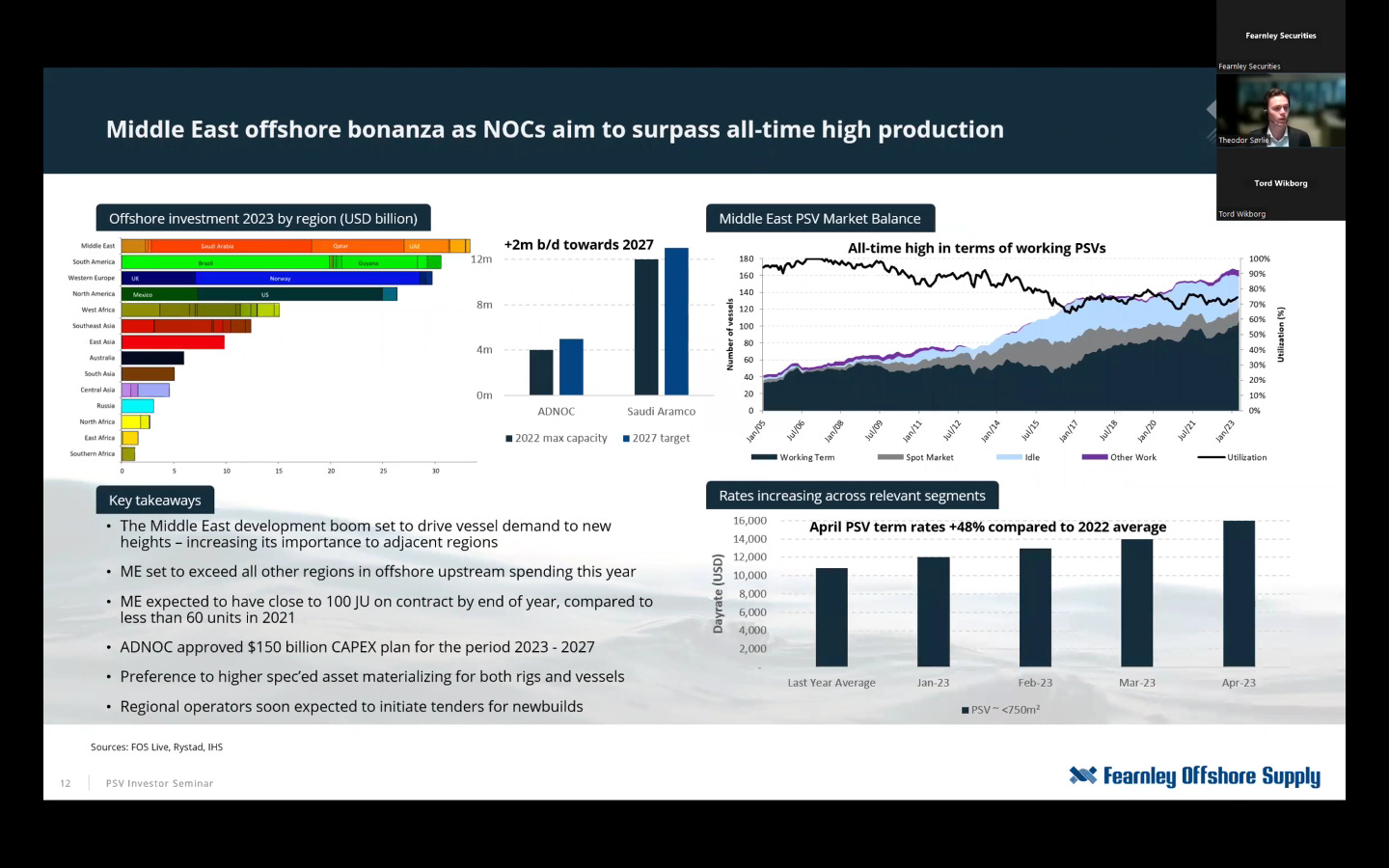

Also mentioning the Middle East quickly. Because the Middle East has basically served as an absorber of tonnage, together with Brazil, in recent years. So, in terms of number of PSVs working in the Middle East, it's the highest number ever now. It has a fleet that's been benefiting a lot on migration from the APAC [i.e. Asia-Pacific] region, specifically Southeast Asia. They’ve taken tonnage from Southeast Asia into the Middle East, but now the APAC region is recovering quite quickly as well. So, vessel owners are less incentivized to taking tonnage into the Middle East.

And this is happening while we're expecting the total number of jack-ups on contract to go from 60 in 2021, to over 100 by the end of next year. So, you see that the market dynamics is basically requiring more tonnage and the excess supply, it's basically gone.

Also worth noting that both ADNOC and Saudi Aramco has a board approval for increasing production towards 2027. So ADNOC is going to increase the production from 4 to 5 million barrels a day, while Saudi Aramco from 12m to 13m bpd. To do this, ADNOC has approved 150 billion CapEx plan for the period this year to 2027. And that's surely going to drive a lot of offshore demand because the onshore resources are starting to reach maturity, and the majority of new capacity in this region is coming offshore.

I mentioned briefly that we're seeing that the excess supply or whatever supply that might be available in the market is not in a good technical state. So, we know that in the North Sea, there's no vessels left in layup. We know that in Brazil, they've taken out everything. The Gulf of Mexico is not that relevant for us because it's operating as a closed market. And you have very few players who can basically set pricing quite favorably for themselves.

So, when looking at the Southeast Asian market, West African market, and Middle Eastern market, let's look at what’s left of the cold stack units.

So, you had almost 170 units in cold stack back in 2017—18. That's now reduced to about 90 units. But when you take out those units and try to understand how old are they and how long have they been in layup, you see that actually the majority are over five years old in Layup and more than 20 or 25 years old of age.

And for us to understand, if you as an operator in, let's say, West Africa, the North Sea, Brazil, you’re Shell or you’re BP: are you likely to give a three-year contract to a vessel that's been laying for five years in West Africa or Latin America or Saudi Arabia, with no maintenance, no supervision? It’s extremely unlikely. So that's why we see the rates accelerating as quickly as they do, because the excess supply is starting to be taken out of the market. And that's why we're also able to be confident on behalf of owners when it comes to rate trajectories going forwards.

A bit on the corporate side: most of you are either steel or equity investors. So, with regards to how the landscape is looking, when the downturn started, there was a lot of consolidation. Banks wanted to improve pricing power, try to consolidate, get operations of scale, and then you’ve had a lot of major transactions going into larger entities in recent years.

So, it started with Solstad Offshore becoming the biggest offshore owner in the North Sea region. That was a merger of multiple companies, and you ended up with a gigantic fleet covering PSVs, OSVs, and Anchor handlers.

They’ve now shifted strategy and sold their PSVs to Tidewater TDW 0.00%↑ , which will make Tidewater the undisputed operator of PSVs globally. You’ve also had Tidewater who bought GulfMark back in 2018 — or it was a merger, but at the end of the day, like acquisition, you've had Swissco, who went bankrupt and went to alliance in the Middle East. You had K Line, the Japanese operator in Norway, who had to sell off their assets to Arura Offshore and Rem. And you had the SPL transaction last year, which might be the best transaction in offshore ever, where Tidewater bought the Swire Pacific Fleet and basically got the PSVs for free.

This is not over. We have a lot of ongoing transactions in the market. We know the French Major Bourbon has been struggling and listed for sale or looking for strategic alternatives going forward. We know Vroon in Netherlands went technically bankrupt and are seeking new owners. We’re working with major transactions for an unnamed offshore operator operating both in APAC, the Middle East and North America. And we saw today that DOF is seeking an IPO with its 55-unit fleet across all segments, including PSVs.

But an interesting development has also been the new entrants, and these are not traditional vessel owners or industry players, but more opportunistic financial players.

So, you have Aurora Offshore, owned by Borealis and backed by among others, KKR. They built a fleet of 16 units now. You have Atlantica Shipping, they have a traditional foothold in traditional shipping, and now they ventured into the offshore world by buying five PSVs. And then you have Standard Supply, which has accumulated a fleet of 9, either fully owned or partly owned PSVs.

What's interesting is that when you look at the chart here, you have more than 25 billion Norwegian kroners that will reach maturity in the coming twelve months and it will be opportunities likely. When this debt is starting to mature and solutions will have to be brought to the table and if that's asset swaps or divestments or remergers, I don't know. But there will definitely be changes going forwards.

Quickly on the historic valuations and how that has developed. I’ve modeled the price or the valuation on a 10-year-old 1,000 square meter PSV. So back in 2012, that was priced at about 260 million Norwegian kroners. It peaked in 2014, just before the market collapsed at almost 300 million. And that ten-year-old vessel is today — as of March 2023 — worth about 240 Norwegian kroner.

With the current rate trajectory we're seeing, and the rates our chartering department is operating with in the North Sea basin, which is basically for next year term rates to reach 270,000 Norwegian kroners, and from the year after 310,000 Norwegian kroners, we see an immediate, or call it obvious upside in current valuations of 35%.

Of course, if you start reaching rates that you see abroad in the North Sea, that will be considerably larger. So, for instance, if you're starting to price assets at the rate achieved of $38,000/day, or even in Australia, we heard that now Shell is fixing PSVs at over $50,000 — of course, with higher OpEx — then we will see these valuations climb even further on the five-year-old 1,000 square meter PSV.

We have a bit of a problem because there has been no new building, obviously. So that [i.e. newbuild deliveries] ends in 2020, because then we don’t have any data points going forward, and we think that will basically be a driver of the valuation of the ten-year-old because there's lack of newer tonnage. The ten-year-old or the seven-year-old will be the preferred tonnage from operators globally. Because the lack of new building is basically creating a situation where that is the only thing you get.

And lastly, a bit on S&P. Last year was an extremely active year. A lot of traditional investors wanted to deploy capital towards the PSV and anchor [handling], especially PSV market. It slowed down a bit in terms of number of transactions this year. We had a banking crisis going on in the US. We have an oil price that's been declining quite a lot since the start of the year, but there's still been quite a lot of transactions on especially larger tonnage. And that's been achieved at on or over $20 million USD.

So, we saw one of the old Havila vessels were able to demand a total all in cost of about $22 million. Quite recently we've seen an unnamed buyer taking out two vessels from a Chinese yard at more than $22 million. The larger assets are being priced into the call it $20m to $25m class, while the medium size done are ranging from $12m to $13m USD.

With the current rate trajectory, it's likely that willingness to pay up will increase. But as of today, there seems to be a bit of a delta that the rates have moved a bit slower than some of the valuations, leading to a difference in the asking prices.

COSL Drilling Europe?

Great read Edward! Thank you. Tight market and getting tighter.