Offshore Wind (1)

US offshore wind, an introduction

As part of my growing interest in Construction Service Operation Vessels (CSOV’s), I have been learning about the offshore wind market in the US. America still lags behind the EU and China in terms of capacity, but it seems like an intriguing growth opportunity for the next decade.

What’s a CSOV? The photo below is an illustration. That tall white cylinder is a wind turbine’s tower which is being installed into the ocean floor.

The first thing to understand about offshore wind projects is that they have long development timelines. Between the pre-option planning process, the site assessment process, then eventually the construction process, it takes approximately 10 years. Because it’s slow and expensive — and the technology continues to evolve — the process is methodical. But this also means that leases and manufacturing contracts are lucrative and tend towards long-term commitments.

To summarize the 3 phases:

1/ Viability, profitability and positive impact studies. Environmental planning; site design; assessment of wind potential; technology review. Feasibility studies before applying for permits.

2/ Design of the facility and construction strategy. Contracts with suppliers (manufacturing, installation of components, turbines, platforms…)

3/ Construction, installation, commissioning and grid connection

This graphic by Iberdrola will help you visualize the complexity of the projects:

On the East Coast of the US, there are currently 27 offshore wind projects in various stages of development. But only two of those projects have received their final permitting approval from the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), which is the Federal Agency which issues permits and regulates these projects. There is a ton of investment on the supply chain side: manufacturing facilities, port infrastructure, and all the other assembly and staging facilities needed to construct the East Coast projects.

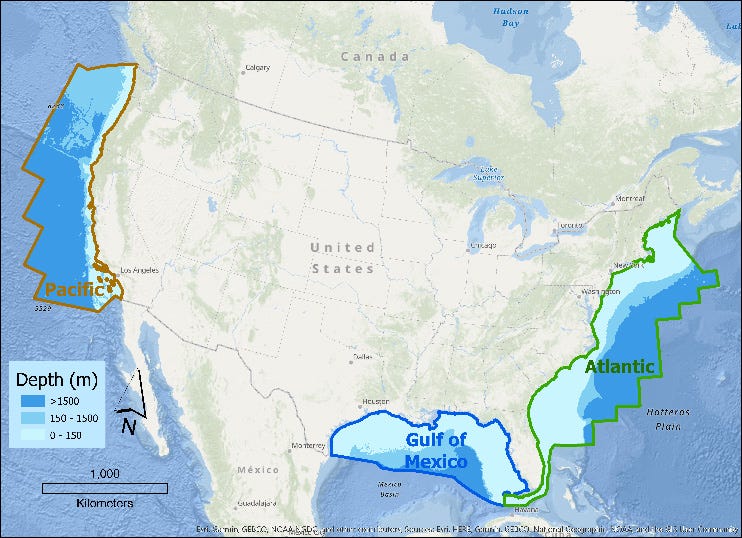

On the West Coast, the process is earlier in the development timeline, and that is because there are challenges associated with developing offshore wind in deeper waters. The waters off the West Coast of the US drop off very steeply versus the East Coast, where there is a wide continental shelf. Therefore on the East Coast, you can build the turbines straight into the seafloor.

The contrast in depth is illustrated in this graphic from the BOEM website:

On the West Coast, it will be necessary to install the turbines on floating offshore wind platforms (FOWP), a large floating platform which is anchored by chains and mooring lines to the seafloor. This allows the structure to move with the waves, but also be located in water depths of 500, 800, or even 1300 meters. It should be noted that this technology is fairly recent; there are only 3 FOWP’s in the world. The first large-capacity floating turbine (Hywind Scotland) was constructed in the North Sea by Scotland in 2017. There is a video about the project by Equinor here. This graphic from Equinor will give you an idea of the massive scale of the undertaking:

There are a number of pilot-projects underway in the US, mostly off of the coast of Maine, where different floating platform technologies are being developed, as well as the best designs for the anchoring systems, the mooring lines, etc.

Platform designs include barge, semi-submersible, spar, and tension-leg platforms. For clarity, some of these are shown below. (I have been reassured that engineers have figured out how to prevent them from tipping over!)

One of the reasons the US is so enthusiastic about developing FWOP technology for domestic use is that the industry is still in its infancy. US engineers and manufacturers have an opportunity to innovate technologies which allow the projects to be commercially viable (they are — as you can guess — hideously expensive as a rule).

Whereas competitors in Europe and Asia have 30 years of experience in fixed-bottom offshore wind farms, and the East Coast US installations benefit from that expertise, the West Coast projects will need new designs. If these new engineering solutions are successful, this may lead to an attractive new export market for US manufacturing.

The current iteration of projects that have been leased by the US Federal Government is moving forward on a fairly predictable timeline, and that is because many US states have set aggressive decarbonization goals. One example is California:

Offshore windfarm projects are very large scale, circa 800 MW to 1.2 GW, the size of a large coal-fired power plant. The demand for electricity from the state governments is solidifying the demand for the development of the projects, which in turn has led to significant supply chain investments. In the past year alone there have been $2.2 billion in investments on the US East Coast including warehousing, port marshaling, vessel investment, to be able to bring the material to the installation sites, and construct the operation.

I know what you’re thinking: “What’s port marshaling?” See here:

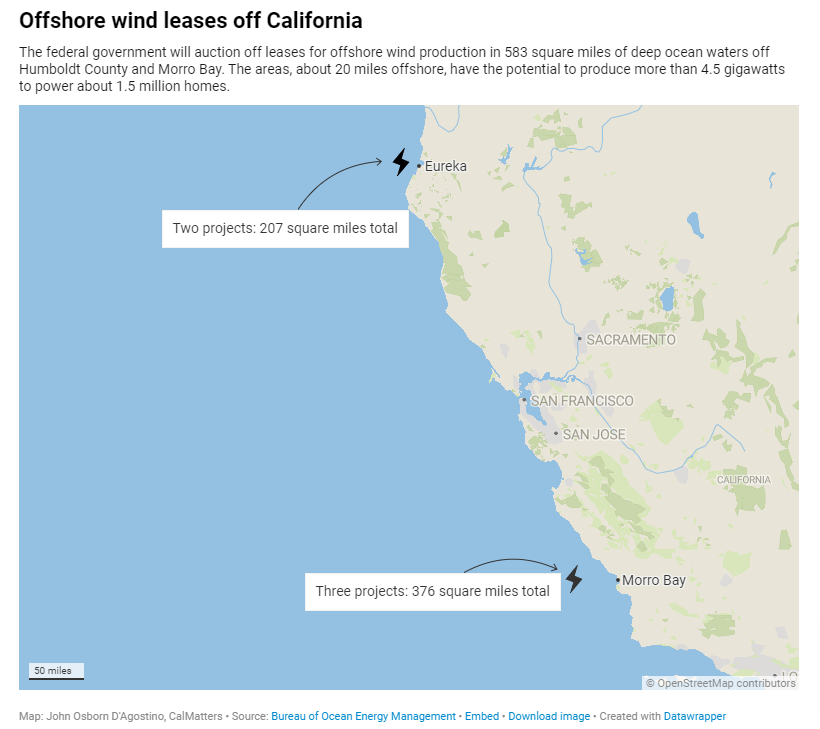

Four weeks ago, the first-ever auction for leases off California’s coast netted final bids of $757.1 million, from companies including RWE Offshore Wind Holding, California North Floating, Equinor Wind US, Central California Offshore Wind and Invenergy California Offshore. Read more via Bloomberg here; several are joint ventures with listed EU energy companies. Experts say construction is at least five to six years away.

If you are wondering where the leased California land is located, see here:

Watch this video for an overview of the California Energy Commission’s plans:

The demand for wind turbines and the vessels that install and maintain them is a growing market:

As I continue my reading about offshore wind, I plan to write more. Subscribe below:

Thanks for the write up, very informative! Would love to see more as you move along in your research!

TNX